Are Ceiling Roses Purely Decorative, Or Do They Serve A Practical Purpose?

Are ceiling roses purely decorative, or do they serve a practical purpose? Discover the history, function and design value of plaster ceiling roses in UK homes.

Ceiling roses are often seen as one of the most elegant finishing touches in a room. Commonly associated with period properties and grand interiors, these decorative plaster features tend to be admired purely for their visual appeal.

However, ceiling roses were never just about aesthetics. Historically, they served practical functions, and even today, they continue to offer both decorative and functional benefits within domestic homes.

Understanding the purpose of a plaster ceiling rose can help homeowners make informed decisions when restoring original features or incorporating new decorative plaster into their interiors.

What was the original purpose of ceiling roses?

Ceiling roses first became popular during the Georgian period and reached peak popularity throughout the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

While they were undoubtedly designed to enhance the appearance of a room, they were originally created to serve a practical purpose.

Before electric lighting became common, rooms were illuminated using gas lighting. Gas pipes needed to run through ceilings to supply chandeliers and pendant lights.

Ceiling roses were introduced to neatly conceal these pipe entries, providing a decorative transition between the ceiling and the light fitting. In addition to hiding pipework, ceiling roses helped protect ceilings from soot marks caused by early lighting systems.

Their shape and positioning helped to disguise imperfections and staining, while also reinforcing the area around heavy chandeliers.

Do ceiling roses still have a practical function today?

Although modern lighting systems no longer require gas pipes, ceiling roses still provide several functional benefits in domestic properties.

One of their main roles is to conceal electrical wiring and ceiling junctions. Even in modern homes, wiring often exits through the centre of the ceiling, which can look unfinished or visually intrusive.

A well-designed plaster ceiling rose provides a clean, elegant frame around light fittings, hiding unsightly wiring and fixings.

Ceiling roses can also help reinforce the area around a light fitting. Larger or heavier pendant lights and chandeliers require strong support points, and traditional plasterwork installations often include structural backing that helps distribute weight more evenly.

Can ceiling roses improve interior design cohesion?

Beyond their practical benefits, ceiling roses play a significant role in tying a room’s design together. In many homes, ceilings are overlooked as design elements, yet they form a large and highly visible surface within a space.

Decorative plaster ceiling roses draw the eye upward and help balance other architectural details such as coving, cornicing, and wall panelling. In period homes, retaining or reinstating original decorative plaster features can preserve architectural authenticity and enhance property value.

Even in modern homes, ceiling roses can create a focal point that anchors lighting features. Contemporary interpretations of traditional plaster designs can introduce subtle character without overwhelming a minimalist interior.

Are ceiling roses suitable for modern homes?

Many homeowners assume ceiling roses only belong in historic or traditional properties. While they are strongly associated with Georgian and Victorian architecture, they can work beautifully in modern interiors when chosen carefully.

Contemporary ceiling rose designs tend to feature cleaner lines, simpler detailing, and more understated profiles. These options complement modern lighting while still adding texture and interest to otherwise plain ceilings.

When installed sympathetically, ceiling roses can soften modern spaces, helping to bridge the gap between traditional craftsmanship and contemporary design.

How do you choose the right ceiling rose for your home?

Selecting the right plaster ceiling rose involves considering the proportions of the room, ceiling height, and existing architectural features.

Larger, more intricate designs tend to suit rooms with higher ceilings and period detailing. Smaller or more minimalist roses often work better in modern or compact spaces.

The size of the light fitting should also be taken into account, as the ceiling rose should visually support the fixture rather than overpower or disappear behind it.

Matching the design to existing decorative plaster, such as cornicing or coving, helps create a cohesive and well-balanced interior scheme.

Do ceiling roses add value to domestic properties?

While ceiling roses are primarily aesthetic features, they can contribute to overall property appeal. Buyers often appreciate original decorative plasterwork, particularly in period homes where architectural details play a key role in defining character.

Rather than being purely ornamental, ceiling roses demonstrate how traditional craftsmanship can serve both structural and aesthetic purposes.

For homeowners seeking to preserve heritage features or introduce subtle architectural detail, a carefully chosen plaster ceiling rose remains a versatile and valuable addition to any home.

What Common Mistakes Do Builders Make With Heritage Plasterwork?

Find out common mistakes builders make with heritage plasterwork, from lath & plaster to decorative detailing, and how to avoid errors on period buildings.

Heritage plasterwork is one of the most visually striking and technically sensitive elements of period buildings. From lath & plaster ceilings to ornate cornices and ceiling roses, it plays a critical role in both the character and performance of historic interiors.

Yet many issues on restoration projects arise not from poor intent, but from misunderstanding how traditional plaster systems work.

For builders and contractors working on period or listed properties, recognising the most common mistakes can help avoid delays, budget overruns, and long-term defects, while building trust with clients, architects, and conservation officers.

Why are modern materials often unsuitable for plaster restoration?

One of the most frequent mistakes is assuming that modern materials can simply replace traditional plaster without consequence.

Gypsum boards, modern fillers, and hard-setting compounds may appear faster and more cost-effective, but they often behave very differently to historic plaster systems.

Heritage plaster is typically lime-based and breathable. Introducing impermeable modern materials can trap moisture within walls and ceilings, leading to damp problems, cracking, and timber decay.

What looks like a shortcut during installation can become a costly defect later, particularly in older buildings designed to manage moisture naturally.

Why is original plaster often removed instead of repaired?

Another common error is defaulting to removal rather than repair. Original plasterwork, even when cracked or partially damaged, often remains structurally sound and repairable.

Conservation best practice prioritises minimum intervention, retaining as much original material as possible.

Stripping out historic plaster not only removes valuable fabric but can also complicate approvals on listed building projects. Skilled plaster restoration allows damaged areas to be consolidated, patched, and blended invisibly, preserving both character and compliance.

Why is lath & plaster so often misunderstood?

Lath & plaster ceilings and walls are frequently misjudged by builders unfamiliar with traditional construction. They are sometimes assumed to be unsafe, obsolete, or inherently defective.

In reality, when properly maintained, lath & plaster performs exceptionally well. It is flexible, compatible with timber structures, and acoustically effective. Problems usually arise from water ingress or poor past repairs, not from the system itself.

Why do decorative plaster replacements often look wrong?

When original cornices, ceiling roses, or mouldings are damaged or missing, a common mistake is installing off-the-shelf decorative plaster that does not match the original profile.

Historic plaster detailing varies significantly by period, region, and even by room within the same property. Poorly matched replacements flatten the visual impact of a space and are immediately noticeable to trained eyes.

Accurate cornice replication, often created from site-specific moulds, is essential for maintaining architectural integrity.

Why is it important to consider movement in historic building renovations?

Older buildings move. Timber frames expand and contract, masonry settles, and seasonal changes affect structure. Heritage plaster systems are designed to accommodate this movement.

Problems arise when builders introduce rigid materials or fixings that restrict natural movement. Cracks then appear not because the plaster is failing, but because incompatible materials have been introduced.

Understanding and respecting movement is fundamental to long-term success in plaster restoration.

Why are plaster specialists often brought in too late?

Heritage plasterwork is a specialist discipline, yet it is often treated as a finishing trade addressed late in the programme. By the time issues are identified, budgets and timelines are already under pressure.

Early engagement with experienced decorative plasterers helps inform method statements, sequencing, and realistic pricing. It also reassures conservation officers and clients that the work will be carried out correctly from the outset.

Why are approval and compliance requirements often underestimated?

On listed buildings and conservation projects, plasterwork is rarely just an internal matter. Many builders underestimate the level of scrutiny applied to changes affecting historic interiors.

Unauthorised removal or inappropriate replacement of plasterwork can lead to enforcement action, delays, or requirements to undo completed work. Understanding the approval process, and planning accordingly, prevents unnecessary disruption.

Why shouldn’t heritage plasterwork be treated as purely aesthetic?

Perhaps the most fundamental mistake is viewing heritage plasterwork as decoration rather than as part of the building’s performance. Traditional plaster contributes to fire resistance, acoustic control, moisture regulation, and structural compatibility.

Ignoring these roles reduces plasterwork to a surface finish, rather than an integrated system. Successful heritage projects recognise that decorative plaster is both functional and architectural.

How Is An Art Deco Plaster Cornice Different From Victorian Detailing?

Discover how an art deco plaster cornice differs from Victorian detailing, and why understanding decorative plaster styles matters for restoration projects.

Decorative plasterwork is often a sign of heritage property character, but not all historic plaster detailing is of the same ilk. Two styles that are frequently confused, or incorrectly combined, are Victorian cornices and Art Deco plaster cornices.

For high-end contractors, understanding the difference is more than an aesthetic concern; it directly affects design integrity, planning approval, and client confidence.

While both styles sit under the umbrella of decorative plaster, they are rooted in very different architectural philosophies.

The design mindset behind Victorian cornices

Victorian detailing emerged during the mid to late 19th century, a period defined by industrial expansion, eclectic influences, and a desire to display craftsmanship and prosperity. Cornices from this era are typically ornate, layered, and expressive.

Common characteristics include:

Deep projections with multiple steps

Floral motifs, acanthus leaves, dentils, and egg-and-dart patterns

Strong classical influences drawn from Greek and Roman architecture

A clear intention to impress through complexity and abundance

Victorian cornices were often designed to act as a visual crown to a room, emphasising ceiling height and reinforcing a sense of grandeur. In many properties, the cornice works in tandem with ceiling roses, corbels, and wall panelling to create a richly decorated interior.

What defines the Art Deco plaster cornice?

Art Deco plaster cornices, by contrast, reflect a dramatic change in architectural thinking. Emerging in the 1920s and 1930s, Art Deco was a reaction against the heavy ornamentation of previous eras. It embraced modernity, geometry, and streamlined elegance.

Key features of an art deco plaster cornice include:

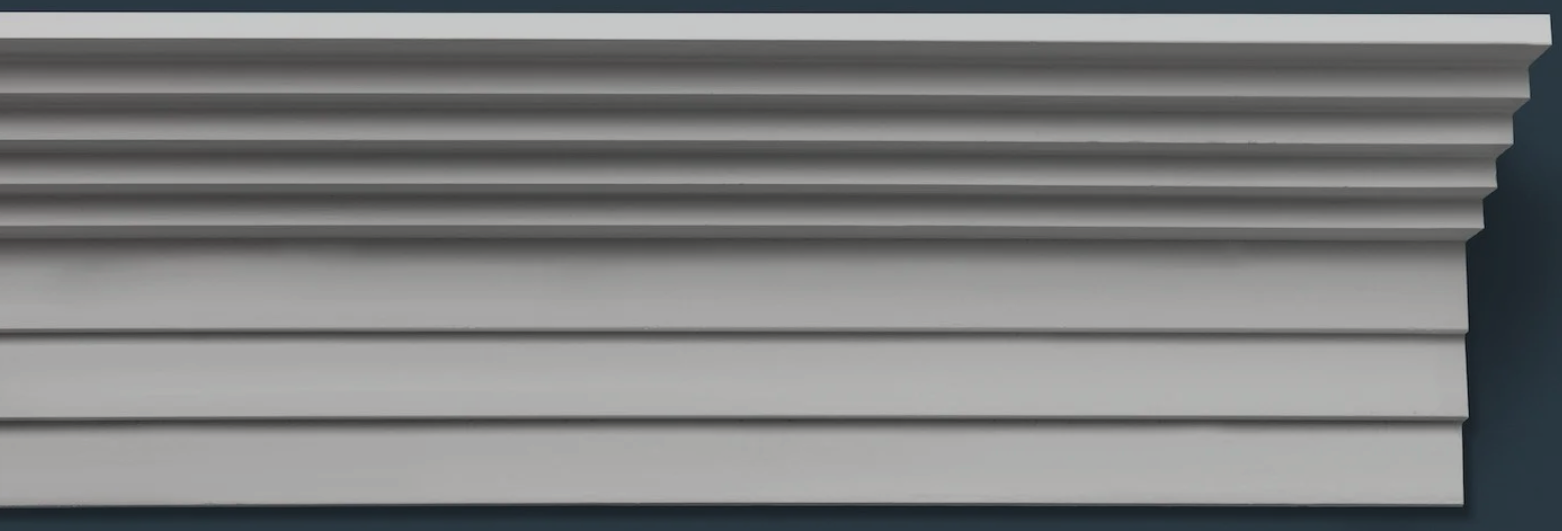

Strong horizontal lines and stepped profiles

Symmetry and repetition

Minimal or abstract ornamentation

Sunbursts, zigzags, chevrons, or geometric reliefs

A flatter, more architectural appearance

Rather than disguising structure with decoration, Art Deco plasterwork often emphasises it. Cornices may still be prominent, but they are controlled and intentional, designed to frame a space rather than dominate it.

Ornamentation: decorative versus architectural

One of the clearest differences between Victorian and Art Deco plaster cornices lies in how decoration is used.

Victorian decorative plaster is additive. Details are layered on top of one another, creating depth through complexity. Art Deco decorative plaster is subtractive. Interest is created through shape, proportion, and shadow rather than applied motifs.

For contractors, this distinction matters when restoring or replicating existing features. Introducing Victorian-style ornament into an Art Deco interior, even if beautifully made, can fundamentally undermine the architectural intent of the space.

How do proportions and scale affect cornice styles?

Victorian cornices are often deeper and more intricate, designed for rooms with high ceilings and generous proportions. Their visual weight suits the grand reception rooms and formal layouts typical of the period.

Art Deco cornices, while sometimes bold, are usually cleaner and more controlled in scale. They work particularly well in spaces where ceiling heights are lower or where the overall interior design is more streamlined.

Understanding these proportional differences is critical when specifying decorative plaster for refurbishments or conversions, especially where original features have been lost.

Why craftsmanship still matters for Art Deco cornices

A common misconception is that Art Deco plasterwork is simpler and therefore less skilled. In reality, precision is paramount. Crisp edges, clean lines, and perfect symmetry leave little room for error.

Victorian plasterwork showcases craftsmanship through intricate modelling. Art Deco plaster cornices showcase it through accuracy and restraint. Both require specialist knowledge and experience, particularly when working on restoration projects or cornice replication.

Conservation and restoration considerations

From a conservation perspective, it is essential to respect the original style of the building. Mixing Victorian detailing into an Art Deco property, or vice versa, can create issues with planners and conservation officers, particularly on listed or locally protected buildings.

Specialist decorative plasterers will often take moulds from surviving sections or reference historic drawings to ensure accuracy. This approach maintains architectural integrity and avoids the “period pastiche” effect that can devalue a high-end project.

Why this matters to contractors

For high-end building contractors, the difference between an art deco plaster cornice and Victorian detailing is not academic; it is commercial. Clients, architects, and conservation officers expect accuracy.

Getting it right builds trust; getting it wrong creates costly rework and reputational risk. Contractors who understand these stylistic distinctions are better equipped to price work accurately, advise clients confidently, and deliver interiors that feel authentic.

When restoring or specifying decorative plaster, accuracy is everything. Working with specialist plaster craftspeople who understand period styles helps ensure the finished space respects the building’s architectural language and meets planning expectations.

Why Do Conservation Officers Still Insist On Traditional Plaster Techniques?

Discover why conservation officers insist on traditional plaster techniques such as lath & plaster, and what contractors need to know for listed buildings.

In an age of advanced building materials, fast-setting compounds, and prefabricated finishes, many contractors understandably ask why conservation officers continue to insist on traditional plaster techniques, particularly on heritage and listed building projects.

From lath & plaster ceilings to hand-run cornices, these methods can appear time-consuming and specialist compared to modern alternatives.

However, traditional plaster techniques are not about nostalgia. They are about performance, authenticity, and long-term building health.

Understanding this reasoning helps contractors plan projects more accurately, avoid costly delays, and demonstrate competence when working on protected buildings.

Why does authenticity matter in listed buildings?

One of the core responsibilities of a conservation officer is to protect a building’s historic character. This includes not just how a space looks, but how it was made.

Original plasterwork, whether Georgian, Victorian, or early 20th century, was formed using lime-based plasters applied over timber laths, often finished with hand-modelled details.

Replacing these systems with modern gypsum boards or synthetic mouldings may replicate the appearance at first glance, but it fundamentally alters the building’s fabric. From a conservation perspective, this represents a loss of historic value.

Traditional plaster restoration, by contrast, preserves the original construction logic and ensures that repairs remain sympathetic to the building’s period.

How does plaster affect breathability and building health?

Traditional lime-based plaster systems are breathable. This is not a buzzword; it is a critical performance characteristic, especially in older buildings. Solid masonry walls, timber frames, and historic brickwork are designed to absorb and release moisture naturally.

Modern impermeable materials can trap moisture within the structure, leading to damp issues, salt migration, timber decay, and long-term structural damage.

Conservation officers therefore insist on lath & plaster and lime-based finishes because they support the original moisture management of the building.

From a contractor’s point of view, this reduces the risk of future remedial works and protects both reputation and liability on high-value projects.

Is traditional plaster structurally compatible with historic fabric?

Older buildings move differently from modern structures. Timber frames flex, masonry settles, and seasonal movement is expected. Traditional plaster systems are comparatively flexible and accommodate this movement without widespread cracking.

Modern plasterboard systems, adhesives, and hard-setting compounds are far less forgiving. When applied to historic substrates, they often fail prematurely.

Conservation officers insist on traditional techniques because they are proven to work within these environments; not just aesthetically, but structurally.

Can original plasterwork be repaired?

A key principle of listed building restoration is minimum intervention. Conservation officers are trained to encourage repair wherever possible, rather than wholesale removal and replacement.

Traditional plaster restoration allows damaged areas to be consolidated, patched, and blended seamlessly into existing work.

Decorative elements such as cornices, ceiling roses, and mouldings can be carefully repaired or replicated using casts taken from surviving sections. This approach preserves as much original material as possible; something modern systems rarely allow.

How does traditional plaster affect visual depth and craftsmanship?

Beyond performance, traditional plaster techniques deliver a visual quality that modern materials struggle to replicate. Hand-run cornices, for example, have subtle variations and crisp shadow lines that reflect skilled craftsmanship.

For conservation officers, this distinction matters. Decorative plaster is not just decoration: it is part of the architectural language of the building. Maintaining that language requires traditional skills.

How do specialist plaster restorers boost compliance and project efficiency?

While traditional plaster techniques may initially appear slower, ignoring conservation requirements often leads to delays, redesigns, and enforcement action.

Contractors who understand and anticipate these requirements are better positioned to deliver projects on time.

Early engagement with specialist plasterers experienced in listed building restoration helps smooth approvals, supports method statements, and reassures conservation officers that work will meet the required standards.

Why this benefits contractors

High-end contractors who embrace traditional plaster techniques position themselves as trusted partners on heritage projects. Rather than seeing conservation requirements as obstacles, they become opportunities to demonstrate technical understanding and attention to detail.

In a competitive market, this knowledge differentiates serious contractors from generalists, and opens the door to more complex, higher-value work.

If you’re tendering for a heritage or listed building project, working with specialist plasterers experienced in traditional techniques can make the difference between smooth approval and costly delays.

Engaging the right expertise early helps protect both the building and your programme.

Is Decorative Plaster Restoration Worth The Investment?

Decorative plaster restoration explained. Discover when restoration adds value, when replacement is best, and why specialist assessment matters in period homes.

Original decorative plasterwork is one of those features people admire instantly, but unfortunately it can lose its charm when it shows signs of age and wear and tear.

Cracks, missing sections or previous poor repairs often lead homeowners to wonder whether plaster restoration is worth the time and cost, or whether replacement would be simpler.

In most period properties, restoration is not only worth the investment; it’s usually the wiser long-term decision.

But like all good building decisions, it depends on understanding what you have, what can realistically be saved, and what value restoration brings beyond appearances alone.

Why do people hesitate to restore decorative plasterwork?

Many homeowners assume restoration will be:

More expensive than replacement

Slower and more disruptive

Aesthetic rather than practical

In reality, those assumptions often come from experiences where decorative plaster has been treated as a finishing trade, not a specialist craft. Proper restoration starts with assessment, not removal, and that changes everything.

Cracks, delamination and even missing sections don’t automatically mean failure. In many cases, original plasterwork has simply moved with the building over time, especially in Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian properties.

Does restoring original plaster add value to a period property?

Yes, and not just emotionally. Original decorative features are a major contributor to a period property’s value. Estate agents, surveyors and buyers increasingly recognise authenticity.

Retaining original cornices, ceiling roses and mouldings helps preserve the architectural integrity of a space in a way that modern replacements often cannot replicate.

Poorly matched new mouldings, incorrect profiles or off-the-shelf coving can actually reduce perceived value, particularly in higher-end homes or conservation areas.

Restoration protects:

Proportions and scale of rooms

Original craftsmanship and detailing

Consistency with the property’s era

Is it cheaper to replace decorative plaster than restore it?

Not always, and often not in the long run.

While replacement can appear cheaper upfront, it frequently involves:

Removing sound original material unnecessarily

Making good surrounding ceilings and walls

Installing profiles that don’t quite match

Restoration focuses on saving what can be saved, repairing damaged areas and reinstating missing sections only where required. This targeted approach avoids over-work and preserves as much original fabric as possible.

In many projects, clients are surprised to find that restoration costs are comparable to replacement, but deliver a far superior result.

What types of plaster damage can actually be restored?

Decorative plaster restoration can address:

Cracked or separated cornices

Damaged ceiling roses

Broken mouldings and ornament

Areas affected by historic leaks

Poor previous repairs

Even when sections are missing, skilled restoration allows moulds to be taken from surviving details so reinstated elements blend seamlessly with the original work.

When is replacement plasterwork the better option?

A restoration specialist will always be honest when replacement is unavoidable.

Replacement may be necessary when:

Original plaster has completely failed

Large sections are missing with no reference points

Previous alterations have destroyed historic detail

Even then, replacement should be informed by the original design, period and proportions of the building; not dictated by what happens to be available off the shelf.

Does decorative plaster restoration disrupt day-to-day living?

Any building work creates some disruption, but restoration is often less invasive than full removal and replacement.

Because the focus is on repairing existing work rather than stripping everything back, dust, noise and structural disturbance are usually reduced. Clear planning and experienced execution make a significant difference here.

A specialist will also advise on timing, sequencing and protection to minimise impact on the rest of the property.

Why does specialist plaster restoration experience matter so much?

Decorative plaster restoration is not about applying new materials; it’s about understanding old ones.

Working across Gothic, Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian properties requires:

Knowledge of historic materials and methods

An eye for proportion and detail

The ability to judge what should be saved versus replaced

This experience is what prevents unnecessary loss of original fabric and ensures any reinstated work sits naturally within the space.

Is decorative plaster restoration really worth it?

If you own a period property and value its character, the answer is usually yes.

Restoration:

Preserves authenticity

Protects long-term value

Avoids inappropriate replacements

Respects the building’s history

Most importantly, it ensures decisions are made thoughtfully, not reactively.

Are you considering restoring decorative plasterwork in your property?

A proper assessment can reveal far more potential than first appearances suggest. Speaking to a plaster restoration specialist early often saves both original detail and unnecessary cost later on.

How Has Decorative Plaster Evolved From Georgian To Contemporary Architecture?

Discover how decorative plaster evolved from Georgian to modern homes, and why period detail still matters for high-end restoration and contemporary builds.

Decorative plasterwork has long been a quiet marker of quality in British architecture. From the restrained elegance of Georgian interiors to the bold geometry of Art Deco and modern clean lines, plaster has adapted to changing tastes while retaining its core value: craftsmanship.

For today’s contractors working on high-end residential or heritage-led projects, understanding this evolution isn’t just academic: it informs better design decisions, accurate restoration, and more successful collaboration with clients and architects.

What are the hallmarks of Georgian plasterwork?

Georgian architecture (1714–1830) was heavily influenced by classical ideals. Interiors were designed around balance, proportion and harmony, and plasterwork reflected this philosophy.

Cornices were elegant rather than ostentatious, often featuring shallow projections, dentils, egg-and-dart motifs and finely modelled profiles.

Georgian plaster cornices were typically run in situ or cast in small sections, using lime-based plaster. Ceiling roses were present but understated, designed to complement chandeliers rather than dominate the ceiling.

The skill lay in precision and consistency: details that today’s restoration projects must replicate accurately to preserve architectural integrity.

For contractors working on Georgian properties, especially listed buildings, matching original profiles is critical. Even small deviations in scale or projection can disrupt the visual balance of a room.

What defines Victorian plasterwork?

As the Victorian era progressed (1837–1901), interiors became more expressive. Advances in materials and mass production allowed plasterwork to become more elaborate, and homes increasingly showcased wealth and status through decoration.

Victorian cornices were deeper, more decorative and often highly individual. Floral motifs, acanthus leaves, scrolls and layered mouldings became common. Ceiling roses grew larger and more ornate, often acting as focal points in reception rooms.

This period presents both opportunity and challenge for modern projects. Victorian cornice replication frequently involves working from damaged originals, partial fragments, or neighbouring properties.

Skilled decorative plasterers are essential here; off-the-shelf mouldings rarely provide the depth or sharpness required for authentic results.

How can you recognise Art Deco plasterwork?

The early 20th century brought a dramatic stylistic shift. Art Deco rejected historic revivalism in favour of clean lines, symmetry and geometric pattern. Decorative plaster remained important, but its expression changed.

Art Deco cornices tend to be stepped, angular or streamlined, sometimes incorporating sunburst or linear motifs. Rather than soft ornamentation, the focus was on bold form and architectural rhythm.

Today, Art Deco plaster cornices are increasingly specified in refurbishment projects and high-end apartments where clients want period character without excessive ornamentation.

Accurate reproduction relies on understanding proportion and shadow as much as decoration.

How is decorative plaster used in contemporary architecture?

In modern architecture, decorative plaster has not disappeared; it has evolved. Contemporary cornices are often minimal, shadow-gap based or custom-designed to integrate with lighting, acoustics or ceiling features.

The emphasis is on precision and finish rather than ornament. Architects frequently specify bespoke plaster details to achieve seamless transitions between walls and ceilings, conceal services, or introduce subtle architectural interest.

Unlike mass-produced alternatives, traditional plaster allows complete flexibility in profile, scale and application.

For high-end contractors, this is where decorative plasterwork becomes a problem-solving material as much as an aesthetic one.

Why understanding this evolution matters on site

Each architectural period carries its own rules, proportions and expectations. Treating decorative plaster as a one-size-fits-all product risks undermining the design intent of a project, particularly in heritage restorations or luxury developments.

Working with a specialist decorative plasterwork company ensures:

Accurate replication of historic profiles

Appropriate materials for listed buildings

Bespoke solutions for contemporary designs

Consistent quality across large or complex projects

Whether restoring a Georgian townhouse, replicating a Victorian cornice, or installing a contemporary ceiling detail, the underlying craft remains the same; only the language has changed.

Craftsmanship that bridges past and present

Decorative plaster’s longevity lies in its adaptability. It has evolved alongside British architecture, responding to cultural shifts while maintaining a foundation of skilled handwork.

For today’s construction professionals, it offers a rare combination of tradition, flexibility and long-term value. When used thoughtfully, decorative plasterwork doesn’t compete with architecture; it completes it.

If you’re planning a heritage restoration or high-end interior project and would like to discuss traditional or contemporary decorative plasterwork, our team is always happy to speak to you by appointment and offer technical guidance and early-stage input.

How Can Decorative Plasterwork Enhance Luxury Interiors?

Discover how decorative plasterwork enhances luxury interiors such as boutique hotels with bespoke designs, craftsmanship, and timeless architectural detail.

Luxury interiors are defined by elegant finishes, and a sense of craftsmanship that feels timeless. One design element that has been quietly but effectively shaping the world’s most prestigious homes, hotels, and public buildings for centuries is decorative plasterwork. =

From hand-crafted cornices to ornate ceiling features and bespoke wall panels, plaster detailing continues to be one of the most impactful ways to take a space from ordinary to exceptional.

But what exactly makes plasterwork such a powerful design choice in luxury interiors, both traditional and contemporary? And how can decorative plaster transform your property?

Why is decorative plaster a timeless feature?

Luxury interiors are defined not just by the quality of materials, but by the craftsmanship behind them. Decorative plasterwork represents centuries of skill.

Unlike mass-produced mouldings or synthetic alternatives, traditional plaster is created, shaped, and installed by hand. Every curve, motif, and line has intention and artistry behind it. This brings an authenticity into a room that simply can’t be replicated by modern shortcuts.

For clients wanting interiors with real character, whether that’s a Georgian townhouse, a modern minimalist penthouse, or a boutique hotel, plaster instantly communicates quality and heritage.

Which interior design styles is decorative plaster suited to?

While many people associate plasterwork with classical or period properties, today’s luxury interiors embrace plaster in a far more flexible way.

Contemporary minimalism

Slimline cornices, shadow gaps, and clean, crisp lines create a refined architectural feel without overpowering a room. Subtle detailing gives minimalist spaces a sense of depth and sophistication.

Modern luxury

Bespoke curved ceilings, geometric wall panels, and large-scale feature mouldings add personality to modern apartments, open-plan living areas, and high-end commercial spaces.

Classical grandeur

For period restorations, decorative plasterwork remains unmatched. Reinstated cornices, enriched ceiling roses, and hand-crafted motifs bring elegance back to homes where architectural features have been lost over time.

Boutique and hospitality interiors

From restaurant ceilings to hotel reception spaces, plasterwork helps create unforgettable first impressions. Bespoke designs allow interior designers to create brand-defining, one-of-a-kind features.

How does decorative plaster enhance architectural flow and balance?

Luxurious interiors rely on proportion and harmony, and plasterwork plays a vital role in achieving both.

Cornices help visually “finish” the meeting point between walls and ceilings, bringing cohesion to the room. Decorative panels can balance wall heights or frame key architectural elements.

Because all plasterwork can be custom made, it allows designers to perfectly tailor the scale, depth, and pattern to suit each space. Whether the goal is to create drama or quiet elegance, plaster provides the architectural structure to achieve it.

How does plasterwork interact with light?

One of the most overlooked luxuries plasterwork brings to interiors is its ability to interact with light. The dimension created by plaster mouldings casts subtle shadows that change throughout the day.

This gives the room movement, softness, and visual interest; qualities that flat surfaces simply cannot replicate.

In luxury settings where lighting design is carefully curated, plaster mouldings can help shape ambience by reflecting shadow, depth, and texture. Even simple detailing can transform the atmosphere of a room.

How can bespoke design be used in decorative plasterwork?

The true hallmark of luxury is personalisation. Decorative plasterwork offers almost limitless opportunities for bespoke design:

Signature feature ceilings

Custom motifs for heritage properties

Unique wall panel designs

Multi-layered cornices

Hand-sculpted centrepieces

Large-scale commercial features

Whether replicating historic patterns or designing something entirely new, plasterwork allows clients to create interiors that feel truly unique. This is especially valuable for architects and designers working on high-end residential or hospitality projects seeking standout detail.

How durable is bespoke plasterwork?

High-end interiors demand materials that stand the test of time. Unlike lightweight alternatives, real plaster is incredibly durable and long-lasting. With proper installation, it can endure for decades, if not centuries.

It resists warping, cracking, and deterioration far better than cheaper options, making it a smart investment that brings lasting value. For homeowners and commercial clients, plasterwork is both a design feature and a long-term architectural asset.

How our expert plastercraft team can help

Whether you’re restoring a period property, creating a modern luxury interior, or designing a bespoke commercial space, expertly crafted plasterwork adds depth, character, and architectural beauty that few materials can match.

If you’re ready to enhance your project with hand-crafted decorative plasterwork, restoration, or bespoke plaster design, our specialist team is here to help. Get in touch today to book a consultation.

Is Your Victorian Cornice Original… & How Can You Tell?

How to tell if your Victorian cornice is original. Key signs to look for, restoration tips, age indicators and expert advice for authentic period plasterwork.

Victorian properties are known and admired for their decorative flourishes: high ceilings, sculpted architraves, bold ceiling roses, and of course, ornate plaster cornicing.

But when homeowners take on a renovation project, one question often arises: “Is my Victorian cornice actually original?” It’s an important question, especially if you’re planning any structural changes, repairs, or full plaster restoration work.

Knowing whether your cornice is original, replaced, or partially replicated can guide your decisions, inform your budget, and help you maintain the architectural integrity of your home. Here’s how to spot the clues.

Look for hand-crafted imperfections

During the Victorian era, most decorative plaster cornice was run in situ or cast using traditional fibrous plaster techniques. This often resulted in subtle, charming imperfections that don’t appear in modern, machine-made alternatives.

Things to look for include:

Slight asymmetry between repeating motifs

Soft edges rather than the crisp, laser-sharp lines of modern cornice

Tiny variations in depth or pattern where sections were hand-run

Signs of layering, where the craftsmen built details in stages

An original Victorian cornice rarely looks “perfect”, but this is part of its character.

Check the material: is it solid plaster or modern composite?

Original cornicing was almost always made from:

Traditional lime plaster

Fibrous plaster using hessian for reinforcement

If you see evidence of these materials, it’s a strong sign of authenticity. Conversely, many replacement cornices from the 1980s onward were made from:

Polyurethane

Polystyrene

Modern composite moulds

These lightweight materials lack the depth and crispness of traditional plaster and can be spotted by their hollow sound and low weight. A professional plaster restoration specialist can usually identify the material instantly.

Look for age-related wear in the right places

Authentic Victorian mouldings almost always show predictable signs of age, such as:

Fine hairline cracks that follow the shape of the cornice

Patina from years of paint layers

Small chips or abrasion in areas like corners, mitres, and junctions

Subsidence-related separation between the cornice and ceiling

These signs aren’t inherently problematic; in fact, they’re often evidence that the moulding has a long history. A mixture of minor cracks and patina usually signals original cornice rather than a more modern reproduction.

Compare it against typical victorian patterns

The Victorian period was known for bold, ornate mouldings. Common motifs included:

Dentil detailing

Rope and bead patterns

Deep coving with strong vertical relief

If your cornice features these enriched styles, it may well be original. That said, Victorian-style mouldings are still produced today, so pattern alone doesn’t confirm authenticity. However, style can be a helpful indicator when combined with other signs.

A specialist can also match your pattern to known Victorian profiles or historical catalogues, which can further validate its age.

Inspect the joints, mitres and fixings

One of the most reliable ways to determine originality is looking closely where the cornice pieces meet. In Victorian homes, the joints were typically:

Hand-mitred, resulting in uneven junctions

Butted tightly, sometimes with slight gaps

Fixed with nails, horsehair plaster or lime adhesive

Modern cornice produced off-site often fits together with factory precision. Perfectly crisp mitres usually indicate a newer installation.

If you can see old fixings or lime-based adhesive behind the moulding, this is a strong clue that it’s original.

Look for signs of cornice alteration or partial replacement

Not all Victorian cornice is fully original. Many homes contain a mix of:

Original sections

Replaced lengths from 20 – 40 years ago

Areas that have been replicated after ceiling repairs

Restored patches where cracks or impact damage occurred

Tell-tale differences include:

A section of cornice that looks slightly sharper than the rest

Inconsistent depth or shadowing

Variation in plaster colour beneath paint layers

One corner or wall run that appears newer or smoother

Specialists in plaster restoration can replicate original Victorian profiles so precisely that most homeowners cannot tell the difference. However, subtle differences may be visible before repainting.

Bring in an expert for a definitive answer

While homeowners can identify many clues themselves, the most reliable way to determine whether you have an original Victorian cornice is to bring in a specialist. A trained professional can:

Identify the era based on pattern and material

Spot historic hand-run techniques

Determine whether the piece is original, partly replaced, or a modern reproduction

Advise on repair, restoration or full replication

This is especially important if you’re planning major works such as ceiling replacements, structural changes or restoration of decorative plaster.

Whether your moulding is fully original or partially replaced, the right care and restoration approach will ensure it lasts for future generations.